IDENTIFY

While artificial intelligence may be possible, we should never allow computers to make important decisions because computers will always lack human qualities such as compassion and wisdom. Or so said Joseph Weizenbaum, the late professor emeritus of computer science at MIT and creator of ELIZA, a computer artificial intelligence program in 1965, in his influential text, 'Computer Power and Human Reason.' Weizenbaum makes the crucial distinction between deciding and choosing. Deciding is a computational activity, something that can ultimately be programmed. Choice, however, is the product of judgment, not calculation. It is the capacity to choose that ultimately makes us human. Human judgment encompasses complex non-mathematical factors, such as emotions and the value they play in our emotional society. Weizenbaum also once said that “history makes us human,” citing it as the sum of our experiences. This interrelationship — between history and humanity — forms our identities, charts both our conscious and unconscious paths through life, and, in the process, creates a mental model that remains beyond the grasp of technological advancement.

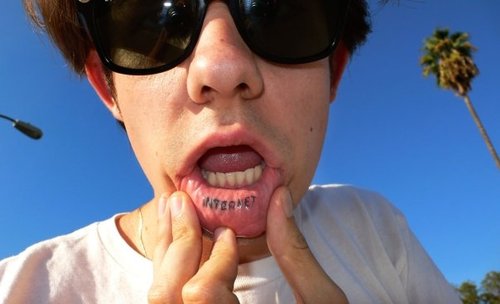

Hearing Weizenbaum’s skeptical take on contemporary artificial intelligence just before his death in the 2010 documentary Plug and Pray, I saw a man afraid of a technology he helped to create. I realized that I was part of the last generation that would ever know a world without the Internet, and that the formative years of my youth were spent in a still emerging space that has fully consumed and nurtured me into adulthood. My position and my future here are both by choice and, I might argue, need. Computers and the Internet have shaped my identity from such a critical age that I cannot seem to separate my online and offline experiences, my history there from my history here.

What has identity become, now that our social selves are laid bare online? How is identity established within the form-fields of Facebook? Our connections are tagged and bound to our profiles. These digital networks have not only transformed our societal structure, they have also re-shaped our internal selves.

THE QUICK ADDICTION

At its core function, the Internet is a tool for the communication of information, whether factual or fictional. It has allowed us access to knowledge we would have otherwise never known, at a rate that we could have never achieved with printed materials. Each tool that we have developed to spread information has exponentially increased the speed at which it travels, leading to bursts of creativity and collaboration that have accelerated human development and accomplishment. The wired Internet at broadband speeds allows us to consume content so fast that any delay causes us to balk and whine. Wireless Internet made this information network portable and extended our range of knowledge beyond the boundaries of offices and libraries and into the world. Mobile devices have completely transformed our consumption of information, putting tiny computers in our pockets and letting us petition the wishing well of the infoverse.

Many people say this access has made us impatient, and I agree. But I also believe it reveals an innate hunger. We are now so dependent on access to knowledge at these rapid speeds that any lull in our consumption feels like a wasted moment. The currency of the information appears at all levels of society. From seeing new television shows to enjoying free, immediate access to new scientific publications that could impact your life’s work, this rapid transmission model has meaning and changes lives. We have access to information when we are waiting for an oil change and in line for coffee. While we can choose to consume web junk, as many often will, there is also a wealth of human understanding and opinions, academic texts, online courses, and library archives that can be accessed day and night, often for free.

We are hungry for more. Does our over-consumption of material goods stoke our appetite? Has our obsession with physical objects changed into an obsession with ideas? It is certainly easier and faster to consume content than things. And this information is infinitely recyclable; it isn’t used up once discarded. Both code and files can become outdated and out-versioned, leaving files and web pages inaccessible, corrupt, or “errored out,” the information contained lost to obsolescence. We have consumed and passed on and traded texts for centuries before and after movable type and digital printing, but even those technologies degrade. Now e-books and PDFs have become the new texts we circulate and archive in our libraries. Our informational experiences are mediated by machines that have changed both the structure of our society and the way we think.

THE SYSTEM

The cognitive process of the computer user is shaped by the architecture of the software with which they interact, whereas its conceptual structure --and its nested storage system of drives, folders, and files — has shaped the collective organizational structure of the user. The new conceptual structure of the Internet has obliterated the contained structure of the single machine.The links between bits of knowledge have been represented visually online, creating a thought pattern that is reproduced ad infinitum in the minds of Millennials throughout the world. The network is embedded in us.

In his new book Software Takes Command, Lev Manovich makes it clear that the graphical user interfaces of the machines we interact with today mask the actual computer system behind with visual metaphors. We are removed from the processing structures and algorithms, which are invisibly executed behind the screen. We understand the metaphor of the machine through software, and this visual metaphor is now a site of creative acts, and have co-opted this form of figuration for creativity. We create machines to compensate for our deficiencies and software to translate our ideas into the language of machines.

TAXONOMY

I have an intricate system for sorting my files on my machine, clear only to me, with groupings and categories that are referential to the meaning I have given the contents themselves. The same group of files can be endlessly sorted by another user in additional configurations, based on the conceptual or literal categories they identify. This personal taxonomy provides a loose structure by which our content is physically represented on our personal computers.

In the cloud, however, the taxonomy is more dispersed, while the common language between media is translated between separate systems and metaphors. An image can be tagged in one manner on Flickr and another way on Instagram. Certain systems poach the taxonomical structure of others (see: the new Facebook tags derived from years of Twitter users, the @ identification system for tagging friends) to provide continuity across services. But the ecosystem itself is disjointed and awkward. I can share all of my tweets to Facebook and vice versa, creating an endless loop of content fed through multiple channels, flooding friends and followers with replicas of replicas of ideas.

THE PUBLIC PERSONA

The persona of an individual is rooted in the group. The persona exists for an audience, whether public or private, and gains context and meaning through its relationship, active or reactive, to this audience. The persona is not the inward self, but part of the public presence. It is the outward-facing schema of our identity.

Facebook has rapidly cemented the concept of the persona in the public realm. Alternate identities, or 'alts,' serve a function for users to achieve a goal otherwise unattainable through their true identity. Some of these alts exist for a single day for a single purpose, an avatar culled for work from various web-sourced materials. Others exist for years, a nom de plume of the computer age. Works and oeuvres may exist under completely fictional identities.

Style is the visual layer of the self, extending to ocular and vocal style, both the pictorial and linguistic representation of an identity. Online, it is the documented 'physical' embodiment of the identity, whether true or alt. The message of identity is corroborated by images and other media. This package of language and image creates a viable context for the persona. From there, the alt reaches out into the social sphere, starting conversations and providing commentary on real accounts. Style facilitates action, providing contextual cover for the troll. This alt identity is the cloak the troll wears to work.

Think about how we describe our life online; we talk about our ‘Internet presence,’ as though our digital comments and posts make us present in another place and time. While we wait in line for coffee or sit on the toilet, we project our Internet presence outward, with no specific relationship to the activity we are physically engaged in. This disembodied projection extends the conceptual reach of the self beyond what a non-connected individual might feel.

VARIABLE IDENTITY

Our world depends upon a completely variable concept: the identity. We need driver's licenses and identification cards to prove our existence. We need photo ID and documentation that we were born into the same world in which we attempt to live. Our names vary between groups. To the government, I am “Krystal Rose South,” but to many I am “KSOUTH,” or various other nicknames based on my identity within these groups. This name is our introduction to most people, a piece of data we put forth countless times to connect with other individuals. In the physical realm, it is a handshake and an offering of the name. Online, the name may be all we know about someone who has reached out to us or that we noticed on the Internet.

This name, whichever and however we choose it, creates an opportunity for a new identity, whether it is rooted in our physical self or not. This is how we remember the early Internet, when users created handles that became their new selves and allowed them to speak freely, disconnected and sheltered from their IRL interactions.

THE BRAND

Identity is a word now used loosely as a synonym for brand. The 'brand identity' is the look, feel, voice, and message of a brand, one disseminated into the world as the public-facing persona of the corporation. Once measured in sales and stock value, a brand identity can now be measured in social analytics and web metrics. The brand's identity is cemented in the market by feeling, the relationship of a user to that specific identity. Brand affinity and loyalty are in relationship to the brand's stories and narrative arc.

With the rise of social media, the personal brand has become attainable for anyone. In the 'open' space of the Internet, individuals have access to the same tools that marketers use to control the brands of giant companies. The Internet is our airport; we are all going through the same security checks and gates. Our collective knowledge of these marketing and advertising tactics has led users to turn the methods onto themselves. Now, digital artists, business owners, and zealous personalities can create Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, and YouTube channels to disperse their generated media into the world under the moniker of a personal brand. They use the same tactics to raise engagement, CTR, and viral sharing. The goals of the individual may differ from the goals of large companies, but the methods and outlets are essentially the same.

THE GAZE

The Internet is a mirror which we gaze into to find new ways of identifying and recognizing ourselves. Whether the goal is communication, consumption, or education, we get out what we put in. Our experiences online are mediated both by the machine and language; the eye and the mind. This is not terribly different from the systems established by previous media, such as film and television. What is radically different—and what has completely transformed our lives— is that we are no longer just consuming. We are putting forth, creating and contributing, and participating in systems from which we receive feedback. These loops of feedback are part of the core structure of computer systems programming, generally, and have become equally integral to the construction of our online society.

But what is feedback? There is the response: you put an idea, let’s say a Facebook post about your artwork, into your social stream. Your friends respond with comments about how nice your artwork is and ask if you have seen another artist’s work. You, in turn, respond. This is a direct feedback loop, one that is essentially the same as real life. A less direct loop is when someone “likes” your art post. You receive a little red notification on your page that excites you. You decide to post another piece of artwork to earn more likes. Another: your friends share your artwork with their friends and now users outside of your immediate network are seeing and liking your work. But to remain in the loop, you must like or comment your own work on this page to keep receiving notifications about who is looking at your work.

PHYSICALITY

Internet users share a physical relationship, one that works off of the network created between machines. These networks have various inputs and points of contact. Some of these relationships are cursory and loose, based only on a shared interest or idea, while others are long-lasting and fruitful relationships that continue to deepen over public or private online interactions. While no physical media may be exchanged, these relationships are often founded on the exchange of information. Whether original content is created — such as words, images, or other media — or the dispersion of information generated by outside authorship, this new economy of information is, at the peer-to-peer level, a mutualistic system, with each individual deriving specialized individual benefits.

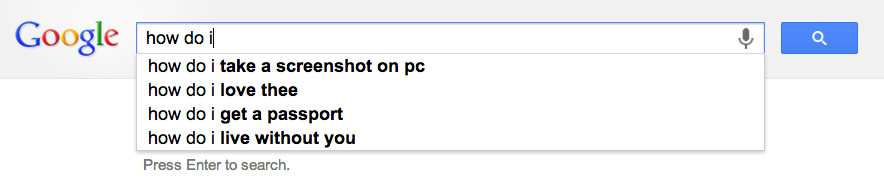

While these relationships may not have physical outputs, the input to the system always requires some physical mediation. This may change in the future, but, for now, we are (mostly) in control of our machines. They require us to tell them what to do and, while the language of computers is not always visible to us as users, they understand our commands because we taught them to.We have imposed our language onto the machines, but, despite this, we have also slowly adapted our language to speak more clearly to them. An example: I used to Google a word and then ”definition” to bring up a dictionary website. I then learned that I can input ”define: word” to ask Google to present the definition to me. Now, Google itself has adapted both methods to produce almost identical results. We are adapting the systems and the systems are adapting to us.

THE BODY

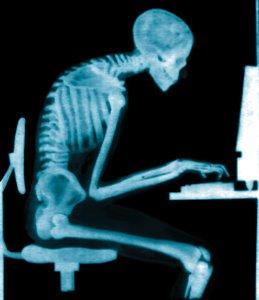

Think of the posture you assume as you gaze at your device. At the computer, we sit and shift for hours on end, hunched and staring, making only tiny gestures as we surf. I move my fingers to control a virtual space that extends far beyond the planar limits of the screen. We extend our dominant hand through the finger, onto the mouse or trackpad. Our physical reach extends into the screen through this cursor.

We hold our smartphones at arm’s length and sometimes squint to see content that is not scaled for human consumption. Our thumbs and forefingers graze the screen, swiping, tapping, and zooming through the software space. Our bodies are always on alert, waiting for the next notification to pull our attention back to the screen. Our dominant arms tire from constantly holding our phone up to our faces.

We feel phantom vibrations in our pockets or as we drift off to sleep at night. We hear an alert and we all check our devices to see who got the message. The sounds are ubiquitous and we allow them to interrupt our most private moments. We are always connected, always listening, always watching for the next piece of feedback that brings us back into the loop of our virtual selves.

These are not the postures of communication. We lose the hand gestures and facial expressions of speaking face-to-face, supplanting them with emoticons and emojis that attempt to bring our feelings back into the mix. We adapt written language to try and get our thoughts across. Extending the shape of the word, repeating letters, CAPS LOCK, excessive punctuation—all these strategies help pick up the slack of our emotionally deficient text-based communication. While we have the ability to cause affects with language, there is a corporeal disconnect between hearing the words “I love you” spoken aloud versus seeing them in 11-point type in a word bubble onscreen.

THE DOX (to CONTROL)

Sometimes all we know of someone is their name. From the name, we attempt to locate more information. At our fingertips, we have access to a giant public database that we can query for more information. Using special qualifiers, we can drill down to search for exact information from specific sites, include or exclude certain data or periods of time. These aren't as widely known as the simple act of putting quotes around a name. The more unique the name, the easier it may be to pinpoint the target, but the more difficult it may be to cull information. The more general name posits a different problem of too many unwanted results, which then need to be filtered by additional keywords tied to known information: location, age, handles, etc. Each known bit of data leads to more data that can be found. This process, called “doxing,” is sometimes referred to as stalking. I see it as informed information gathering generally linked to contact by the individual.

Aware of these methods, many people have chosen to never post personal information online, while others attempt to delete the information that already exists. But information and images can make it into the world without your consent or knowledge. More importantly, they can be used in unintended ways, without your consent or knowledge.

Compounding these challenges, a user’s image or name can be used to create an identity that they have no knowledge of. This second self, whether true identity theft or the appropriation of an avatar and name by a net bot, can generate its own content under your name, perpetuating an existence completely separate from you, and completely out of your control. This darker side to the control that we have over our internet identities can have impact on our offline lives.

LIFE=GAME

We see this come up quite a bit in the realm of online games. Online gaming has been taking place since the dawn of the Internet, with text-based MUDs evolving into graphics-based MMORPGs. These games allowed users a flexible identity associated with their gameplay. If a player was banned from the system, he or she could create a new identity and start fresh. Stemming from “Dungeons and Dragons” and similar role-playing games, they were generally linked by their structure and goals. Though I am no expert on the history of these games, two games stand out in my mind as breaking this model.

The first is “The Sims,” a PC game that made the leap to the Internet in 2002. The goal of “The Sims” is to create a virtual human avatar which you clothe, feed, send to work, and perform other basic actions for (including going to the bathroom, showering, and sex). You just have to keep your Sims alive and happy, and they reward you with...living...and Simoleons, the Sim currency. Now available on almost every platform, this is the best-selling PC game of all time.

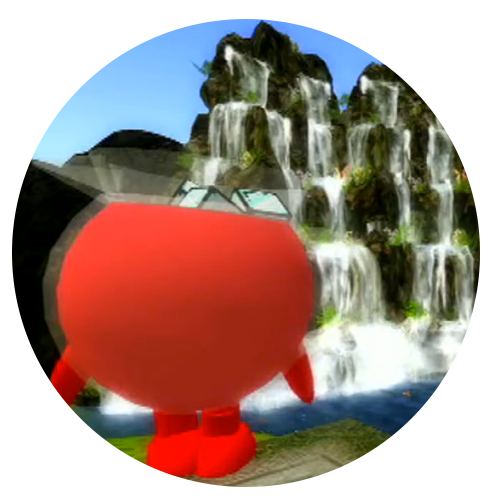

The second, released in 2003, is “Second Life,” an online game that allows users, or ‘residents’ as they call themselves, to create avatars that navigate endless worlds. There is no goal beyond exploration, socialization, community formation, and the trade and sale of user-generated 3D objects to modify the game world itself. By 2010, 21.3 million “Second Life” accounts had been created, but Linden Labs, creators and maintainers of the game, don’t publish statistics on active users.

Both games involve the transference of identify into a virtual space that, in effect, mirrors our own. The control of the user is complete; he or she can create, manipulate, or destroy their characters without consequence to their real lives. They can engage in play and socialization that may be restricted in their real lives, providing cathartic experiences that are free and open-ended. They push the idea of escape, present in all media consumption, to an active role over which they have control.

The players of these games have developed extensive and active communities. While they may never meet in real life, they play with each other online for years or decades. A large part of “Second Life” seems to be the satisfaction of fetishes in a 3D virtual world, with users developing characters that play out their fetish role in the space of the game. For example, users can act out their desire to copulate with a unicorn in this space or conduct virtual orgies through their avatars and text-based chat.

The artist Jon Rafman conducted virtual tours through “Second Life,” taking people on voyeuristic journeys through the anonymous, sexualized spaces of the game and showing non-players some highlights with the tour guide of Kool-Aid Man, the avatar that Rafman created for himself. The availability of these virtual selves to act on fantasies which are distanced from reality – for instance sexual experiences with mythical creatures, bestiality in general, vorarephilia, flying, etc.– allows a disassociated catharsis. Rafman likens this online experience to a return to an amniotic state, a desire to be completely immersed, similar to full immersion in an online life.

THE ACCIDENTAL AUDIENCE

Another Internet feedback loop was recently covered very well by artist, writer, and educator Brad Troemel. In his essay, “Athletic Aesthetics,” published online via The New Inquiry, Troemel examines the dispersion methodologies employed by Internet native artists, as well as the competition for the increasingly scarce resource of attention that now controls our interactions.

Artists now can (and do) create artworks that they immediately disperse through their social streams to their audience. They take part in the above feedback loop which transpires within social networks. But something else starts to take place: the criticism of this work also takes place immediately, creating an extremely rapid critical response to works. These critics distribute their ideas in many of the same venues of the artist themselves, as well as the artwork. The work, artist, audience, critic, and criticism all coexist in the same network, transmitting to and from each other in an ever-widening loop of feedback. What Troemel points out about this process is that it “...has reversed the traditional recipe that you need to create art to have an audience. Today’s artist on the Internet needs an audience to create art.“

The idea of attention is also key to Troemel’s point about the ‘aesthlete,’ in that our often shallow and overwhelmingly numerous online interactions are all fighting for the same attention. This means your foodie pics and someone’s artwork are appearing on the same Facebook/Tumblr/Twitter/YouTube/etc. stage. His essay contains great insights on the effect this attention economy has on the work and the identity of the artist, and another essay, The Accidental Audience, which also appeared in The New Inquiry,further explores this topic through a project Troemel, et al, executed on Tumblr, called “The Jogging.”

For the project, Troemel looked closely at the Tumblr platform as a distribution method for artworks. The format of Tumblr allows users to post media (image, text, video, etc.) in a stream that can be viewed on their Tumblr page as well as on the Tumblr dashboard by followers. Users/followers can then “like” these posts, as well as “reblog” them to their own pages. This method enables extremely rapid dissemination with attached metrics for tracking the vitality of the post. What Troemel points out is that, while the audience of the original blog may be aware of the context in which the image is presented, the more the image is reblogged, the more obfuscated the meaning may be to the audience it reaches. While the images on “The Jogging” were created with an artistic intent and purpose, that may be stripped and confused as the image travels further down the Internet rabbit-hole. But new meanings are developed; users can attach their own comments to the image, presenting a new context while reaching a new audience of followers.

The question Troemel presents is: What happens to the art? Is it changed by these shifts? Does it retain the same power? “The Jogging” is a perfect test for this, as the works presented , at their core, challenge the nature of images and authorship. Composed of found and remixed product photography, the images on “The Jogging” are charged with new meanings, which, according to Troemel, fills an important role in the Tumblr ecosystem: “On a social network flush with recycled posts, there’s a premium on delivering original content for others to share.”

Tumblr has also given rise to the popularization and bastardization of the word “curation.” Once used solely within the context of art, as a practice of organizing and arranging works within an exhibition space, the word now denotes any collection of images or things in a single place. The popular web application Pinterest has become a form of ”curation,’ with users creating thematic boards to which they pin their collection of sugar-free desert recipes or summer wardrobe selections. No longer about identifying a common thread among disparate works, the term has completely lost its grounding in an art context. While many Tumblrs and Pinterest boards do retain some part of the word’s original meaning, hearing mothers and business people use the term in relationship to tagging disparate content has surely soured in the mouths of those with master’s degrees in curatorial studies.

TO SPEAK

“We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed.”

--Michel Foucault, Other Spaces

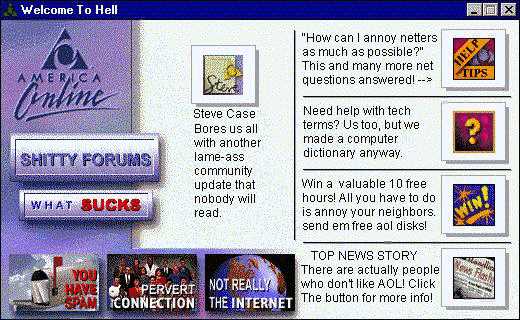

Since the beginning of the Internet, there has been a lot of talking. Not strictly speaking, but chatting. In 1550, to ‘chat’ meant “to converse familiarly.” It has remained in steady use with consistent meaning since that time. While it makes sense that this term was used in the early Internet days, it does surprise me that it still endures, since its more contemporary meaning equates to vapid, passive conversations between acquaintances. AOL gave birth to an accessible chat interface that became incredibly popular and culturally familiar. Before that, chatting online still required deeper computer knowledge on Usenet, IRC, and BBS, with some understanding required to set up the network and join rooms and boards.

America Online started as an Apple BBS in 1989, then was released for DOS in 1991. In 1993, with the release of Windows 3.1, America Online (and other ISPs) became available to the millions of people buying personal computers for the first time, making Internet chat a much more common occurrence. A language already established by earlier systems propagated into AOL. These rooms allowed up to 23 people, keeping the communities small and the conversations manageable. Users could privately message each other or conduct their conversations in a public space, returning back every day to engage with their community in various rooms. But you had to know what rooms to join and then establish the identities of the users without any concrete evidence that what they told you was true.

This space of open and private talk mirrored real-life conversations in all of their excitement and boredom. Chatting became a way of life for many users who spent their time on computers anyways, now accompanied by a steady real-time stream of chatter to be consumed or ignored. AOL chat became AOL Instant Messenger, a service application downloaded and used by millions. Users created avatars and handles like in AOL chat rooms, but now had the ability to keep a list of buddies that did not have to be part of the same room to engage in conversation. This direct mode of messaging made it much easier to keep tabs on friends and to see who was online and offline at any given time.

The identity of the chat user could be formed on the fly, with separate names and logins to form different identities. One could give as much or as little information about themselves as they wished, and go so far as to lurk — that is, to never engage but occupy space and observe the conversations of others. The practice of verbalizing your identity in text, rather than speech, surely changed the way that many computer users thought about themselves. One could expose only the positive aspects of one’s personality or only the negative, forgetting to mention spouses or children or parents, slightly changing your own age, appearance, etc.

Sexualized chat, or “cybering,” became a new form of eroticism and adultery. Real-time text-based chats of explicit nature between two unknowns, exciting two bodies composed entirely of language in a virtual space. Users could invent a new sexuality online, severed from their social body, engaging in thoughts and ”actions” that might cause problems in their day-to-day lives. The foundation of the Internet is all fetish, an exploratory space for people to connect on fringe interests of both sexual and the most banal subjects. Communities are formed around common interests and goals, and the many fetishists of the world were able to find themselves online and explore their feelings in a safe, private space, building a community of like minded individuals with whom they did not have to feel ashamed.

What I am getting at is that these were not just chats such as what you have with the coffee shop guy, these were heavy conversations dealing with the deepest, darkest, most intimate parts of human identity, and these conversations happened with individuals of unknown authenticity. But this did not negate their power or their meaning. The medium of chat became just another vessel for humanity, and all of the darknesses and joy contained therein.

LANGUAGE OF LOL

Now commonplace, the language of chat and other text-based communication has completely changed the level of rigor in our use of words. I know that I can get a point across quickly and easily with the use of acronyms that may or may not be understood and other casual effects that make up the new Internet-English LOLspeak we are most likely familiar with today. While many may see this cyberspeak as a degradation of language, I consider it almost a necessary evolution, however annoying it may be in the midst of maturing. Obviously, we have always adapted language to fit new contexts and times. If we spoke Old English with incredible formality, we would all go crazy. The Internet has leveled the playing field in language, allowing anyone to take on the terminology that once only served niche groups and audiences. “LOL” is a great example of a term that has lost some meaning, even over such a short span of time. When used, it is most likely that the user is not genuinely “laughing out loud,” but more that the acronym has come to represent laughter in any sense. You can spend five minutes on Facebook and find it used in comedic or negative situations with the same effect. Where the number of “ha’s” in a “haha” used to denote how “funny” something was, LOL now replaces it with a general symbol of amusement in any situation.

Is this sort of language really about efficiency of communication? Or is it about being in the know, able to translate the slang type of the new Internet world order? There is a kinship to be found in communicating with secret languages. We see these dialects of language develop around sports, food, art, or music, and Internet-speak has long been cliquey and exclusive, back to 1337 speak, an orthographic language of the very early web. These modes of speaking feel, for a period of time, indecipherable to the outside, protecting the speech of the users under this mask. The language of the community keeps the group tightly bound 2gether.

THE FETISH

Alfred Binet, a French psychologist, proposed that fetishes were either founded in ‘spiritual love,’ rooted in the mind, or ‘plastic love,’ rooted in the body or object. Psychology is full of reasoning about the source of these fetishes and whether they should be nurtured or abandoned. There is a rule that exists about the Internet: if you can imagine a fetish, such as dumping yogurt into trousers for autoerotic purposes, it exists in some form online. Since its beginnings, the web has been a place of connection for niche interests, whether it pertains to training a cat to shit in a toilet or more explicit human shit curiosity. Whether it is finding images that depict the fetish or meeting individuals willing to participate in a fetishistic act, the Internet has become a network serving these communities and the emotional needs that gird them.

Outside of the sexualized fetish, the computer and the Internet, though not an object in the strictest sense, have also become fetish objects. These objects of desire, the objet petit a of our virtual times, serve as a medium between our desires and the actions that they execute for us. While the Internet can provide us with places to buy creature comforts online, it cannot actually deliver these comforts in any direct sense. And while we continually place our trust in our machines to organize important data that we wish to remember, these machines are not immediately accessible to our memories. We must always use the mechanical mediator to access these things and information, even if it is deeply personal in nature, something we see as part of ourselves.

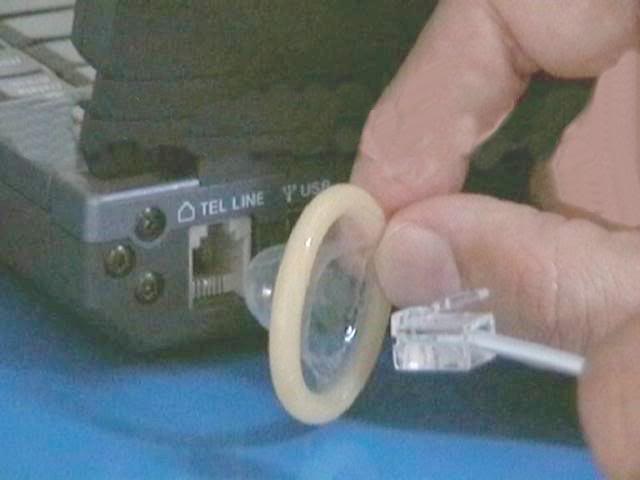

Buying the fastest, most efficient machines makes us feel faster and more efficient ourselves; we see these objects and processes as extensions of our own ability. Our thought processes have become more and more structured around access to these machines at any moment. I don’t need to write down the list of addresses for the events I plan on attending; I know I can get them from Facebook and use the mapping capabilities of my iPhone to find the way. And what happens when we run out of power or drop our device into the toilet? We feel lost. We are afraid that we won’t know when someone is trying to reach us. We are disconnected.

Figure 1: Andrew Norman Wilson, The Inland Printer - 164, part of Scan Ops, 2012. Inkjet print on rag paper, painted frame, aluminum composite material.

Figure 2: Andrew Norman Wilson, Why is the No Video Signal Blue? Or, Color is No Longer Separable From Form, and the Collective Joins the Brightness Confound, 2011, HD Video, 10 minutes.

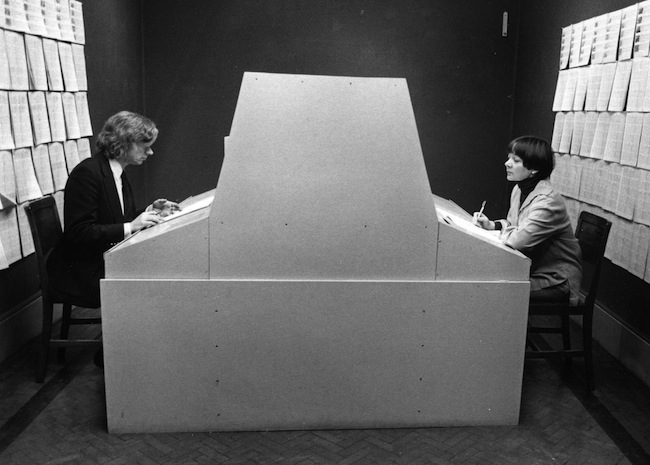

Figure 3: Stephen Willats, Meta Filter, 1973-75. Painted wood, Perspex, computer, slide projector and problem book. Collection of Fonds National d’Art Contemporain, Paris. See also.

Figure 4: Ryder Ripps, Internet Therapy, 2010, website and audio.

Figure 5: Petra Cortright, sickwoof.mov, 2011, YouTube video.

Figure 6: Parker Ito, Parker Cheeto: The Net Artist (American Online Made Me Hardcore), installation view, 2013.

Figure 7: Anthony Antonellis, Facebook Bliss, 2012, website.

Figure 8: Daniel L. Williams, Sweet Treatz, 2009, YouTube video.

Embedding disabled by request.

Figure 9: Jon Rafman, 9 Eyes, Ongoing, website.

Figure 10: Jeremy Bailey, Don't Mouse Around, 2006, YouTube video.

Figure 11: Dina Kelberman, I'm Google, ongoing since 2011, blog.

Figure 12: Jon Rafman,Kool-Aid Man in Second Life-Tour Promo, 2009, online video.

Figure 13: Eva and Franco Mattes, No Fun, 2010, Online Performance.

This video was banned from YouTube.

Figure 14: Claire L. Evans, Digital Decay, 2007, video animation.

Figure 15: AIDS-3D, OMG Obelisk, 2007, Younger Than Jesus @ New Museum.

Figure 16: Bunny Rogers, Pones, ongoing, digital photographs.

YOURSELF

In the documentary film TPB AFK, about the prosecution of the administrators of file torrenting site The Pirate Bay, founder Peter Sunde says on the stand, “We do not like the expression ‘IRL.’ We say ‘Away From Keyboard.’ We think that the Internet is real.” When I heard this, it expressed so succinctly something I have felt since I was 12 years old: the Internet is not only real, it is human and now so totally integrated into our privileged lives and thought processes that we barely even notice it. I have witnessed this shift, realizing I am part of the last generation to experience Life Without Internet. I extend my decision-making process into the ether and extend my social self through wireless, endless social networks, 4G, et al., turning the processing of some parts of my life, and the site of my memories, over to machines. We are no longer tethered to the keyboard, with access to smartphones bringing the reality of online life into our pockets, our cars, our beds.

I believe that because of the historical moment I first got online, and my rapt attention to online matters ever since, with increasing intensity, that my identity is almost half machine. My co-evolution with this technology has instilled a fiercely personal identification with the concept and structure of computers and Internet-based systems within me. This position is not by accident, but choice. I felt something in my early years of being online that I could not describe or communicate to others who had not felt it – that the content stored online, and the makers and distributors of this content, understood the impact it was about to have on the world and aimed to steer it in a positive direction.

While many seem to experience their Internet lives as a separate space of reality, I have always felt that the two were inextricable. I don’t go on the Internet; I am in the Internet and I am always online. I have extended myself into the machines I carry with me at all times. This space is continually shifting and I veer to adjust, applying myself to new media, continually gathering and recording data about myself, my relationships, my thoughts. I am a immaterial database of memory and hypertext, with invisible links in and out between the Internet and myself.

THE TEXT OBJECT

I would sit for as long as I could and devour information. It was not uncommon for me to devour a book in a single day, limiting all bodily movement except for page-turning, absolutely rapt by whatever I was reading. I was honored to be literate and sure that my dedication to knowledge would lead to great things. I was addicted to the consumption and processing of that information. It frustrated me that I could not read faster and process more. The form of the book provided me structured, linear access to information, with the reward for my attention being a complete and coherent story or idea.

Access to computers and the Internet completely changed the way that I consumed information and organized ideas in my head. I saw information stacked on top of itself in simultaneity, no longer confined to spatiotemporal dimensions of the book. This information was editable, and I could copy, paste, and cut text and images from one place to the next, squirreling away bits that felt important to me. I suddenly understood how much of myself I was finding through digital information.

THIS ARTIFACT

I’m not that smart, I always just tell people, “I like smart things,” and I believe interest and curiosity can overpower pure intelligence any day. I’m not a great writer, I’m constantly Googling things I write to make sure I didn’t just read them somewhere, and I know I’m never doing the subjects I take on full justice. But they get me, and there was a point in my life when I realized that I’m probably not going to be an expert at anything but that the things I put out into the world had an audience, and that connecting with people in this way felt so real. I have my history recorded, even if my view is narrow. These logs, both online and on paper, are evidence of a desire to be understood, and trace the development (ongoing) of my identity.

I use the Internet just like everyone else, as a tool for research and fact-checking. I use it to store my evidence, the photos, videos, documents, and miscellaneous files that I collect on my Internet journeys. When I meet someone new, I find myself offering up this digital history to relate to them. I have stored so much of my life online that when I want to tell someone about something that happened, I usually have some photo on Flickr or YouTube video that captures this moment. I offer it up as tangible proof for that which I would fail at describing.

But where does that leave us? Are we losing the richness of our experiences and memories because we know we can depend on blurry iPhone photos to supplement our memories? The art of describing something is lost to the digital artifact of a real experience. A great example of this is going to a concert and watching the audience hold their phones up to record the show. They are looking at a real experience mediated through their machines, capturing evidence to remember something by, remaining outside of the present moment to capture a document of the experience. We are so used to these mediated experiences that we feel the need to perpetuate them, to capture this evidence, proof that we were there.

THE ART SET

My experience with art has always been taxonomical. A new artwork or artist is introduced into my world and all the other artworks I have ever seen get subtly rearranged in my mind, now linked to this new work. My network continually grows, as I find artists through other artists. This network would still exist without the Internet, but its growth would move monumentally slower. Social networks have compounded this; I can find someone’s artwork, find their Facebook page, send them a message, and very quickly be having a conversation with them about their work.

The gallery-sanctioned contemporary art world has always been cliquey and exclusive; it’s the myth I grew up reading about and it still exists, even in such a supportive community as Portland. Social networks, between artists and otherwise, have always been about who you know . Online social networks just bring that to the forefront and, by doing so, break down some part of this system. When anyone can connect with anyone and everyone shares the same framework to present themselves, such as Facebook, a certain democracy develops.

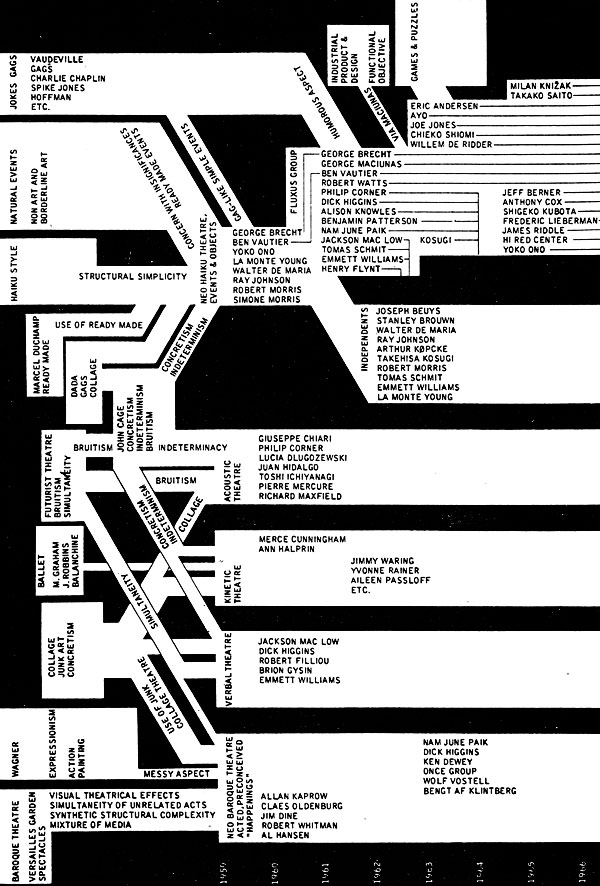

The same group of artists can be endlessly sorted into new social networks, based on the concepts or execution of their work. Some groups may identify themselves through video media published on YouTube and Tumblr, while other may identify with each other through found and altered online images. New factions and movements appear and populate at a rapid pace, with Facebook groups, group Tumblrs, and online galleries and exhibitions being established to disseminate ideas and work. While these groups may extend themselves out of the Internet realm to execute IRL shows in physical galleries, the percentage that do are still relatively small as compared to the massive amounts of work created and distributed exclusively online.

THE PUBLIC VEIL

While I may be physically intimidated by someone IRL and not want to tell them about how much I love their work, the mediating veil of online interaction feels completely comfortable. Not to say that online activities don’t have real world effects; there is no denying that they do and, below, I’ll try to explain a little more about how real this all is, but it sure is easier to speak from behind the mask of the Internet.

Some of my favorite human beings have come to me in this fashion. I found the work of Krist Wood through another Internet artist, Ryder Ripps, who was mesmerized by Wood’s work and carefully composed identity. I reached out to Wood on Google Chat after spending a lot of time with his online output. One of the first things he said to me was, “Identify yourself,” a command to explain who I was and what I wanted. It is a fair request in contemporary Internet culture, where often people receive friend requests from strangers with no context. I found myself able to summarize my existence into G-Chat, into the context of what I knew about this other person, what I thought he might want to know about me, where I saw our identities overlapping.

Through Krist, I learned about Computers Club, a group of Internet artists assembled by Wood who posted their works into a collective stream. I began my online friendship with many of these artists, all working with varying levels of identity manipulation. Some created work under a false name, but made completely different work IRL under their real name, while others kept their new name and work the same across both contexts. This group of artists became an important part of my online life and eventually I realized that their effects extended completely into my real life. I traveled to Louisiana to meet a number of them, merging these online relationships with tangible physical ones. Meeting them made me realize that I had seen them truly online, even their alt identities, that they had allowed me see them this way. They matched up in their physical selves, with all of their quirks and idiosyncrasies.

I recently lost one of these friends, Daniel Williams (aka MOM or maman), and when people asked me how I knew him, I replied, ”the Internet,” and I realized that cheapened the relationship in many people’s eyes. But I met him in real life, so we were Real Friends, but I already knew that long before I saw him in the flesh. I spent so much time with this human being online, on IRC and TinyChat and Facebook, that I didn’t miss a beat when we met at the New Orleans Airport. The chats just continued. All of the jokes and memories were there, just given a voice and a body.

And now all that I am left with is his online record, no physical place anymore, but his Internet presence and epic legacy remain. It feels so shameful to have to defend the depth of my ties to this human due to our mostly “long-distance” relationship, to find out about his death through Google Chat. His very real death has caused me very real pain, one still mediated by the machine, but without this machine I would never have known how beautiful and amazing he was. My mourning has taken place on YouTube and Vimeo and Twitter.

INTERNET PRESENCE

I got on the Internet at age 12, a time I recall being incredibly pivotal and traumatic per general physical tween-ness and awkward mental growth. I think I had grown six inches in a year, figured out what a period was, and was allowed to stay home alone for the first time, life-changing experiences completely eclipsed by my acquisition of a 56k modem and a Netcom account set up by and shared with my dad. I first learned to surf and got a library book with kids’ websites listed in the back. I tired of this in a single day. I found, through my shitty ISP tool, Usenet. I didn’t understand how to find newsgroups, so I searched for things I was interested in, which at the time was probably, #1 horses, #2 the Louvre, #3 Stephen King. I used Internet Archive Wayback Machine a few years ago to trace my earliest Internet times and took this screenshot of what appears to be my first public post in alt.books.stephen-king.

I have spent probably half of my life, at this point, on computers, usually on the Internet (post 1997). The membrane between my online and day-to-day life has gotten thinner and thinner over time. Many punctures have occurred, with increasing frequency.

The Internet people whom I have collected over the years are as much a part of my identity as my 4th grade teacher and afk best friends. They may know things about me that people whom I interact with daily may never know, because those secrets felt safer enclosed behind the glass of the screen, the distance between. Some of them knew me before I used my real name online. In the beginning, it felt powerful to be able to hide behind an alt where I could be treated like an adult if I wanted to.

MERGE

I began posting content to the Internet under my own name around 2003. I wanted to unite a collection of disparate Internet identities, to merge these digital bits with my physical self. It felt like an adult gesture, to take ownership of the content that I was meekly putting forth.

As my identity developed and Web 2.0 happened, I began archiving much of my daily experience on the Internet in various forms. I posted my photos to Flickr, kept links with Delicious, blogged in various places, uploaded to Vimeo, tagging and naming my content, organizing it into sets and streams. My interests, usually researched and documented in detail, became a part of my public output, establishing a brand identity of plants, animals, the Internet, and art. These are the things I am doing, thinking about. I have developed a community of people that also appears to be interested in these things, or in me doing these things; I may never know them, or know that they are paying attention, but they have a steady stream of my content to ingest. This brand of interest has brought me a community of friends, both online and off, that feel some response to the bits I put out.

I realize I am a cog in a vast machine of content being developed and distributed online, but, at the same time, these elements will persist after me, that my brand will, in effect, live beyond my time. I don’t know who will find it or what it will mean to them, or where it may eventually end up. My output submits to the indexical nature of the web, being found by those who seek to find it.

OUTPUT

When I was not reading as a kid, I was writing, hunched over spiral-bound, wide-ruled notebooks with turquoise RSVP pens scribbling adjective-laden prose and poetry. In these pages, I came to find myself, to develop the language and style I still probably cling to today. But these documents, these words, were only for me. I had no context into which to insert myself, just an overflow of thoughts triggered by what I had read and seen.

Finding the Internet gave me a context into which I found myself fitting naturally. I joined a teen poetry newsgroup and began posting my poems, requesting C&C, or “comments and criticism,” asking strangers with no credentials to basically break my tweenaged heart. I valued this feedback, though it was not the motivation for me to create work. I truly believed, as I still do, that making things and recording my thinking was the real reason I was around in the first place, that it was something I Had To Do To Be Happy.

Today, we get feedback on so much that we put online, whether we want it or not. Every Facebook post, Tumblr entry, Flickr photo, and Tweet has systems of feedback in place for the audience to react and respond to your output. We are aware of these potential effects when we make these posts. Luckily, safeguards exist to moderate this feedback by deleting comments or the post itself. We can eliminate unsightly feedback as easily as we can create the content that garnered it. This process of self-editing is not new, but in the age of screen-caps, with the amount of attention people expend grooming their digital feeds, monitoring these streams seems equally important.

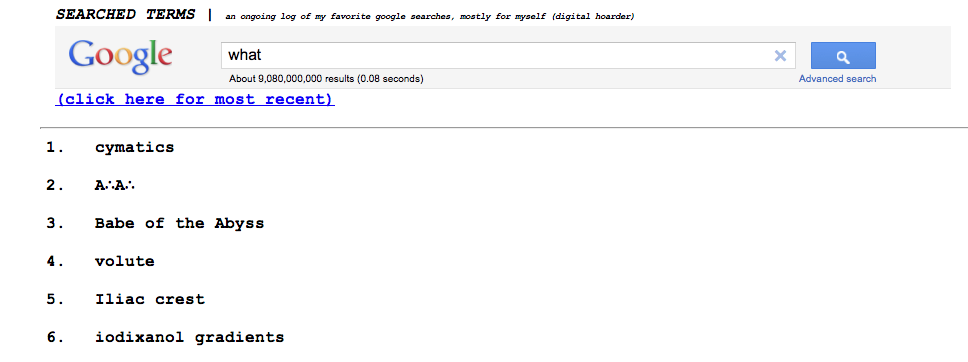

SYSTEM SEARCH

I always tell people that you get out of the Internet what you put in. This has varying levels of meaning. When searching for something, your results will only be as good as your search terms, and the more specific your terms, the closer you can come to finding exactly what you think you are looking for. I also mean this in a deeper way. I’ve already revealed the trust that I have put into this human network and how deeply I regard the connections I have made online. This has led me to even deeper relationships and experiences with people I may have never had the chance to know without the Internet.

“Seek and ye shall find,” has a new meaning online, where the potential for discovery has become global and dissemination can occur in an instant. When I begin researching a new idea or project, I am aware that deep within the Internet there is probably someone else, if not a community of people, who are already having conversations that I would want to take part in. It is so rare now to get zero results in a Google search, but, even if you do, you are aware that the language that you are using may just not fit what you think that you are looking for. We now have the ability to search without language, using Google Image Search with Similar Images, where users can input an image from the web or their own machine to conduct a search using Google’s image analysis algorithms.

The ability to reach out and find information and people and to do so in a system that facilitates response has transformed the limits of our thinking. I (perhaps foolishly) believe that anything I want to learn or know, or whomever I wish to find, is available to me. This concept changes my approach to everything from boiling an egg to learning how to write code to finding someone to be in a relationship with.

EVOLVED?

Before I made artwork on computers, I was a painter. Long hours in small rooms hunched over a canvas moving tiny brushes around with toxic paint were marked by the cracking bones in my body, eventually giving in for the day when my arms shook. I was a terrible painter, but the work always felt good, being able to form ideas in layers, the process of adding and subtracting parts to form a whole. Teaching myself Photoshop heavily increased my time spent on machines, clicking away to create and modify images, again in layers, tweaking effects to create an infinite array of images from nothing but pixels. The work always felt good and it felt fast. I was no longer watching paint dry. I was no longer stuck in a single time and place to create work. I was free to fuck with images and ideas whenever I wanted, to save them to create a different version later, to delete them and start over.

This process is still dependent on my physical body. I must move the cursor somehow to show the machine where I am looking; I must input levels and text; and I must be able to see the screen to know what I am doing. In the not-so-distant future, these limitations will begin to be lifted and removed. The lines between the body and the machine will begin to break down and, probably slowly, though maybe rapidly, the lines between IRL and Internet will begin to blur and dissolve for everyone with access to these tools. What will happen to our bodies? Will we shift to return upright, to less time sitting stagnant in front of machines?

I will admit that I am hopelessly addicted to my computers and phone. I find myself tethered to them, watching the ebb and flow of content and people come and go. I plan ahead so that I have access to power to keep my machines running. I feel desperate as I watch the power drain from my device. I head home at 15% battery life, or bring my chargers with me, beg for outlets, mourn the lost moments when my phone dies. And it’s not because I am expecting a call or that I’m afraid someone won’t be able to get a hold of me. It’s because I am terrified of losing connection to my virtual self, of losing access to the answers to my questions. This information is a part of myself, my device is a part of me, and the space of the Internet feels like home.

CONTROL

I remember filling out questions when I joined OkCupid and one of them took me by surprise: do you Google someone before you meet them? I have always assumed that everyone followed online trails the same way I did, looking for information about the people they meet on the Internet. I’ve since realized that my particular attention to online search results of friends, acquaintances, and complete strangers is not the norm, but it is also not a rarity. I value research and like finding out what people have to say about themselves and the world. I don’t pretend that everything is fact or up-to-date. I just enjoy getting a picture of the individual’s Internet self, their presence, their web vibes. I don’t usually call people out on what I find, but if they do bring it up, I may casually mention, “I saw that on the Internet.”

I search myself, as well, as we all should periodically do to maintain a clear picture of how others might find us online. Sometimes things turn up that I have forgotten, a long lost blog post or video posted that brings me back to a vision of my former self. I can trace my digital evolution; I can pinpoint painful or joyful moments, correlated to metadata and the people who engaged with the content. I am periodically self-conscious; what will my clients find, what will my parents see, what will my potential future-husband learn about my past from this Internet archaeology? In some cases, this history is editable and malleable, able to be deleted or hidden, in others, I am stuck with the result, but able still to bury it beneath new, proud content.

I once noticed a spike in viewership of a few photos I had taken during a photoshoot of me cutting my own hair. Curious, I looked at the analytics attached to the images, which told me what site the views were coming from. I found myself having to create an account for an online message board to view what the posts were about, learning that they had been found and posted by someone to a board dedicated to a previously unknown to me fetish of women cutting their own hair. I found this simultaneously appalling and hilarious. I could take the images down from Flickr, thus ending their fun, but knew that if people really got off on these images, they had probably already downloaded them to their personal archives. So I left them, because that’s just how the Internet plays out. The most banal selfies become the pornography of the diverse fetishist. If I was afraid of this association I would have to remove every image of myself I’d ever posted from the web, but, still, hundreds of photos exist that I didn’t take and don’t have control over. C’est la Internet vie.

GAME=LIFE

Playing video and computer games has been a part of my life since before I was even aware of the Internet. I would spend hours playing Duke Nukem, Doom, and Castle Wolfenstein on my PC, lost in the dark passageways of the first-person shooter. I played against the machine, fighting algorithmic characters programmed to destroy me. My strategies evolved as I learned the levels of the games. Once these patterns became routine, the game lost its power over my time and attention.

Playing games online, competing against other human beings, means that there is no clear pattern. New opponents have their own strategy, strengths, and weaknesses. Every game has its own goals and measures of success. Some games require teamwork while others require the player to think alone on their feet. Does this sound familiar? It is not so different from the real world. Even abstract games that take place in a fantasy world have some grounding in reality and link back to our basic human desires: to advance, to dominate, to prevail. I have played games to forget my real life, to take my active mind to a place of known limits, to a place where I can start over if I fuck up, where there is a task I know is possible to complete.

Playing games for so long has made it harder for me to consume passive media such as film and television. I feel stuck in someone else’s device, someone else’s decisions. The game creates a context for choice and outcome, a world where one thing always leads to another and where there are limited physical consequences . When I feel stuck in my life, I don’t want to then get stuck in someone else’s vision of life; I want to manipulate life into becoming something I control. This desire to have input into the system that came from playing games as a child persists now into my Internet approach.

When our lives become unmanageable, we turn to whatever we can find to try and regain control. For some that is drug addiction, self-harm, or hurting others, but there are hundreds of millions of people who have found catharsis and control in games. There is a constant push and pull in life between chaos and order; we are surprised by random turns of events because we expect cause and effect. But we can never take every element into consideration; there is always some outside influence that we can’t see that impacts how our lives turn out. In a game, the world is finite; the outcomes are contained within the system that has a beginning and end. What is random is programmed to be that way.

THE INTENDED AUDIENCE

I’m not going to lie: I am doing this for myself. My work has always been self-serving, trying to tie down my thoughts to some recognizable form. My struggle with writing has always been its finite nature, as though once the words are written and printed, the idea can’t continue to change. But I know it will keep morphing and I will have to write it all again. Even if no one reads it, I keep trying to clarify and refine in some external form the things that have formed me. The origin of my work is in the diary, notes to myself on how I see myself. As a child, they were cute pink notebooks with locks to which I always lost the key, to sketchbooks with poems taped inside, half-full and still kept out of some need for personal reflection. The Internet is now my diary, dispersed across so many sites and machines that I cannot measure its breadth.

From the earliest days of the Internet to today, sites such as Diaryland and LiveJournal have served as the repositories of teenage angst and victory. These sites function as digital journals. The journal or diary is deeply tied to the development of the human historic record since the development of written language. Stemming etymologically from the Latin term for ‘day,’ the record of personal events onto paper has surely been a factor in the development of personal identity for long enough that it is only natural that their legacy carry over to the digital realm. The format of these sites, ordered by date, does not stray far from physical tradition and follows the form of the archive, documenting notable events. Claudio Pinhanez’s Open Diary project, kept from 1994 through 1996 on MIT Media Lab, was one of the earliest Internet diaries. Eventually platforms such as LiveJournal made it simple for users to create diaries without knowing how to code. This content, whether updated or forgotten, remains online in perpetuity.

I recently found a LiveJournal I kept for a very short time — about a year- -- from from age 18 to 19. It is mostly an archive of romantic emails sent between myself and a long-distance Internet interest. I removed any identifying information at the time when I posted, so I only found it by Googling a very specific line I remembered writing. Finding this archive, now lost in an old email account I’d rather let die, made me realize how widely scattered my Internet presence had come to be and that a large part of my history was peppered across the Internet. I have put a lot of myself out into the world, some of it anonymously, now somewhat lost to me. I kept a blog on a site organized by my friends from 2003 until I had it taken down in 2008. Of course, a record of what once was is still available in bits and pieces on archive.org’s Wayback Machine, which has archived more than 260 billion web pages since 1996. How much of my path from childhood to adulthood is contained within this publicly accessible archive?

I now spread myself across various spaces, maintaining niche Tumblr sites and web pages for each of my pet projects. While intended mainly for my own personal record, these sites have an audience and this audience has no real context for my reasoning behind these posts. The diary is now public and left to its own devices. I give up control over this content when I post it and this lack of control has taught me much about being an artist. It is beautiful to see your ideas transferred onto someone else, to see something you made communicate, to connect with another human. The creative act longs for viewership, for reception.

No effort is meaningless. No creative act is without purpose, even if this is unknown. We have reasons for what we do and, deep down, expectations. While these may not be met in the way that we expect, something is bound to happen. We speak so that someone may hear us; we listen in hopes of a response. Life is full of surprises, and the Internet, begot of all our lives, is ripe for discovering these surprises. This potential for discovery – once limited to meeting someone and asking the right questions, or someone publishing their ideas – is now open to anyone who can get online.

TO CHAT

“We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed.”

--Michel Foucault, Other Spaces

I realized something only recently about the nature of chat and what its structure has imposed on my mind. I can have as many conversations at once as I can handle. In a group chat, everyone can speak at once. In audible conversation, this would be rude and impossible to follow. Online, it is the norm: , constant multitasking, surveying a vast domain of sites, windows, and tabs. Chat gives space to think before you commit to speaking, allowing the user to mull over their words before sending the message. Conversations may linger over days, even weeks as chatters go online and offline. I can send messages that may not be visible until the receiver logs back in at an unknown date, the message kept in Internet stasis until that connection is made. These simultaneous, instant, and delayed modes of speech are in direct opposition to our physical interactions with people.

We have all felt the terror when something intended for private conversation is broadcast in a public context. The moment we accidentally send a DM to the public, then scramble to delete the tweet; the moment we Skype into the wrong window; or preemptively send a drafted email, attach the wrong file. We worry about people talking behind our backs, gossiping about our private lives, making assumptions. And now our lives are public. This anxiety of an audience exists as part of our collective conscious, FOMO, and fear of being observed incorrectly.

Where verbal conversations leave room for interpreting the meanings of words, chat and text conversations leave an even wider space: there is no facial expression, no closeness, no intonation, emphasis, space. The pain of receiving a ‘K’ or thumbs-up emoji response to an outpouring of emotion is familiar. Or the confusing situation where you are texting with someone for a long period and then you try and call them and they don’t answer and you just hang up without leaving a message because WTF is their deal? But we’ve all done it, too.

Where once news spread like wildfire through the stoop gossip of stay-at-home moms and two daily editions of the newspaper, now we all get breaking news headlines from the New York Times app on our iPhones while we are in meetings. We spend the days sharing information, videos, news, meals, with each other in the form of URLs and posts that show up in various endless feeds. We receive a tailored aggregate of the information we have chosen to subscribe to, much of it noise that crowds out genuinely useful information.

The veil of the chat allows us to hide our emotions, revealing them only when we are ready. I worked on a project with my (Internet) friend Krist Wood, a work called sadf, that touches on this very beautifully. Composed of four long shots of myself and three other young women, all of whom make works on or with computers, it depicts us crying while Instant Messaging with an unknown character(s). The text of the chats is in direct opposition to the emotions we reveal in the soft glow of the computer screen. The hands, the messengers of the words related through chat, are disembodied from our very real tears.

We are familiar with and open to crying in front of our machines, exposing them to our darkest emails and stalking habits. My connection to these women and to the artist would be highly unlikely without the Internet, but these people, and the things I have learned from them over years of online time, are invaluable to me.

The essay which accompanies this video work sums up something which I, too, have come to realize over my lifetime: that this change I’m feeling is real and recognized by others.

“Though there have been a few social technologies that have begun to confound or make abstract our means of sensing one another (such as the written letter), the present age of computers and the Internet (and all of its associated communication technology) represents a profoundly new set of biological circumstances and selective pressures for the evolution of social behaviors. Using the computer for locating, identifying, and communicating with other people (particularly using text) provides a fundamentally different biological situation for humankind; one in which we are no longer seeing and hearing other human beings in the way for which we've been fine-tuned by evolution.”

SELF-TALK

I feel as though I have seen language transformed in my short life. Does every generation feel like this, watching words and meanings fluidly change? I think in short bursts, tweet-length text messages, brand slogans, and song lyrics. I constantly doubt the authenticity of my identity, chalking it up mainly to place and circumstance, and the consumption of so much media that I sometimes confuse which way I consumed it. I transpose and combine the plots of films and books and articles, surely misinterpret a large amount of what I consume; but here I am, some whole human being with my own say in the matter.

This idea of choice in the context of identity has always fascinated me and I deeply admire people who approach themselves with wild abandon, adopting new ways of being and thinking the way I’d change my shoes . High school was, of course, especially ripe with this: the band girl gone goth, the football guy turned stoner. Identity sometimes feels like a dress code, whether business casual or weekend soft pants or first date, something that I can use to hide or expose myself.

I say terrible things that I learned on the Internet. I use embarrassing, mistyped English probably more than I would care to admit. And I have been known to use emoji to attempt to express complex feelings to loved ones. I let the Internet finish my sentences, when I begin to speak and realize that the rest of the thought I left somewhere online, finding it after a quick, quiet search on my phone under the table. I sit with my machines by my side all day, every day, because I know that when I ask them for something that they will listen and do what they were made to do (the only thing they can do) and try to provide me an answer. I am bound to my machines by this language, but it is also the barrier to our unity.

THE ABSENCE

Freud saw the fixation of the fetish as an overcompensation for an absence. Art history has taught me that a ‘fetish’ is an object worshiped for its powers. I’ve identified the computer, and the access it gives me, as a personal fetish. Of course, the root of all Freud is sex, and the root of all art, if you ask me, is the object. I see the computer as the perfect merger of these two definitions: the totalized whole replacement onto which so much of one’s self, both reality and fantasy, can be projected. This vessel contains all of us.

What lack motivates our easy entrance into this digital sphere? What are we missing, that we all seem to be trying so hard to make up for? I have suffered many personal losses, turning inward when I cannot grasp control over the world around me. And where do I turn? To the computer, to the Internet, to the information, where I can be alone and yet not alone, surrounded by constant activity as I sit perfectly still and solitary. The same instinct that drives lonely people to busy public spaces drives us here. My loneliness, stemming from alienation, drives me to the most open space. While some say that this web only deepens our isolation, I find solace here, in objectless, infinite space.

My relationship to this system is complicated and ongoing. My dedication and passion, hope and belief, come in waves escalating above a particularly high norm. The world will change, but our connections online will only deepen, our dependence and symbiosis will continue to evolve. But into what? Will our acceleration normalize? Will Moore’s Law continue to prove true? Will we transfer more of ourselves, of our lack, into this fetishized space until we realize the lack has shifted poles? What happens when the power runs out, when we get disconnected? Where will we have left to go?

THE END TO THE END

There is a system, and there are people within this system. I am only one of them, but I value deeply the opportunities this space grants me, and the wealth contained within it. We must fight to keep the Internet safe and open. Though it has already lost the magical freedom and democracy that existed in the days of the early web, we must continue to put our best minds to work using this extensive network of machines to aid us. Technology gives us so much, and we put so much of ourselves back into it, but we must always remember that we made the web and it will always be tied to us as humans, with our vast range of beauty and ugliness.

I only know my stories, my perspective, but it feels important to take note during this new technical Renaissance, to try and capture the spirit of this shift. I am vastly inspired by the capabilities of my tiny iPhone, my laptop, and all the software contained therein. This feeling is empowerment. The empowerment to learn, to create, and to communicate is something I’ve always felt is at the core of art-making, to be able to translate a complex idea or feeling into some contained or open form. Even the most simple or ethereal works have some form; the body, the image, the object. The file, the machine, the URL, these are all just new vessels for this spirit to be contained.

The files are beautiful, but I move to nominate the Internet as “sublime,” because when I stare into the glass precipice of my screen, I am in awe of the vastness contained within it, the micro and macro, simultaneously hard and technical and soft and human. Most importantly, it feels alive—with constant newness and deepening history, with endless activity and variety. May we keep this spirit intact and continue to explore new vessels into which we can pour ourselves, and reform our identities, shifting into a new world of Internet natives.

SEE ALSO:

The people who make up my internet community.

kristwood.com

computersclub.org

petracortright.com

dinakelberman.com

jonrafman.com

parkerito.com

thisket.com

andrewnormanwilson.com

meryn.ru

newrafael.com

jodi.org

paintfx.biz

122909a.com

jeffbaij.com

beafremderman.com

bodybybody.net

nateboyce.net

jeremybailey.net

jacobciocci.org

wwwtxt.org

danielrehn.com/

martin-cole.blogspot.com

nicolascolon.com

seecoy.com

stephd.biz

caitlindenny.com

dismagazine.com

likeneveralways.com

michaelguidetti.info

therealannhirsch.com

joelholmberg.com

justinkemp.com

briankooser.com

idalehtonen.com

theageofmammals.com

duncanmalashock.com

byobworldwide.com

ryder-ripps.com

bradtroemel.com

artievierkant.com

jonathanvingiano.com

clairelevans.com

rhizome.org

travesssmalley.com

dump.fm

spiritsurfers.net

taborrobak.com

bmruernpnhay.com

constantdullaart.com

youmakemesohappy.blogspot.com

out-4-pizza.livejournal.com

amaliaulman.eu

adamcruces.com

stadiumnyc.com

worse.tumblr.com

laurenelder.net

alexandragorczynski.com

briankhek.com

micahschippa.info

ninawenhart-cv.blogspot.com

jennifer-chan.com

alexmackindolan.com

alexanderpeverett.com

christianoldham.com

israellund.com

datacorruption.org

lindsayhoward.net

louisdoulas.info

momarie.com

doubleunderscore.net

krystalsouth.com

netartnet.net

manuelfernandez.name

domenicoquaranta.com

lisaradon.com

319scholes.org

linkeditions.tumblr.com

tcour.com

karenarchey.com

eai.org

internetarchive.org

pica.org